July 24, 2018

Problems with CRISPR

CBC past awardee and CBC Tech Day speaker, Brad Merrill, UIC, discovers a mechanism behind CRISPR gene editing imperfection

Brad Merrill, UIC, and his collaborators have recently published in Molecular Cell their new findings which explain why CRISPR gene editing sometimes fails to work. The authors discovered that the Cas9 protein can bind to the DNA at the cut site in two orientations. One of these orientations unfortunately causes Cas9 to get “stuck,” thus preventing the initiation of the DNA repair. This important finding should help researchers achieve increased enzyme-editing efficiency in the future. Merrill, the senior author on the publication, has several links to CBC: in 2014, he received a CBC Catalyst Award and participated in the CBC Tech Day as an invited speaker. Merrill was also a mentor to a CBC Scholar, Brian Shy, Class of 2013. Congratulations to all scientists involved in this pivotal discovery.

Biochemists discover cause of genome editing failures with hyped CRISPR system

UIC today | by Jacqueline Carey | July 10, 2018

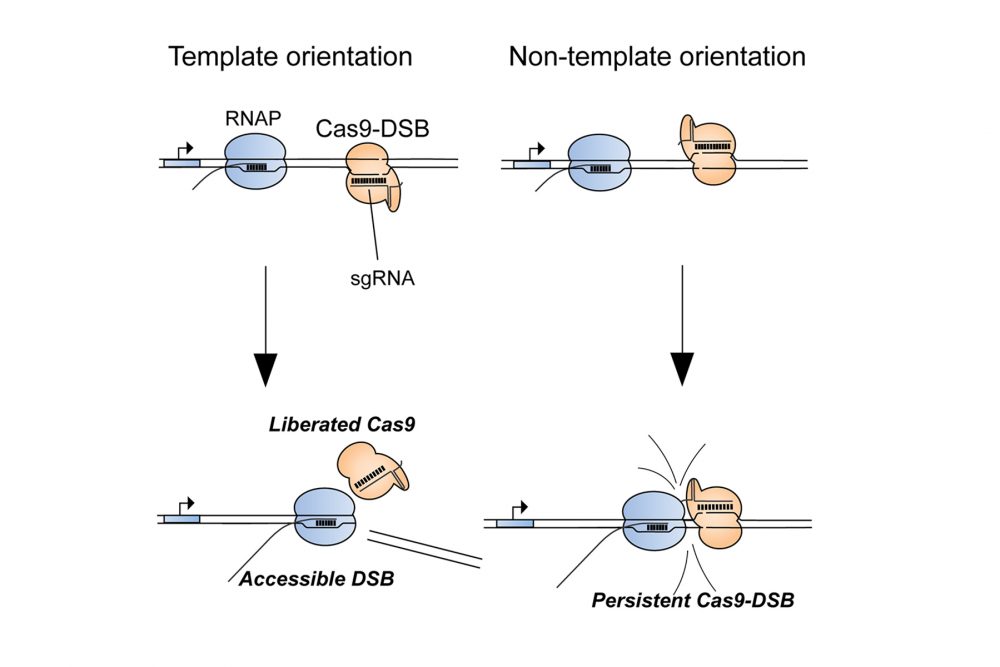

UIC researchers show persistent Cas9 binding to a double strand break causes CRISPR genome editing to fail about 15 percent of the time. When RNA polymerases collide with Cas9 from one direction (template orientation), they can dislodge Cas9 and increase genome editing efficiency. Courtesy of: Clarke R, et al.

Researchers from the University of Illinois at Chicago are the first to describe why CRISPR gene editing sometimes fails to work, and how the process can be made to be much more efficient.

CRISPR is a gene-editing tool that allows scientists to cut out unwanted genes or genetic material from DNA, and sometimes add a desired sequence or genes. CRISPR uses an enzyme called Cas9 that acts like scissors to cut out unwanted DNA. Once cuts are made on either side of the DNA to be removed, the cell either initiates repair to glue the two ends of the DNA strand back together, or the cell dies.

In a study published in the journal Molecular Cell, the researchers showed that when gene editing using CRISPR fails, which occurs about 15 percent of the time, it is often due to persistent binding of the Cas9 protein to the DNA at the cut site, which blocks the DNA repair enzymes from accessing the cut.

Senior author Bradley Merrill, associate professor of biochemistry and molecular genetics in the UIC College of Medicine, says that before now, researchers did not know why the process randomly failed.

“We found that at sites where Cas9 was a ‘dud’ it stayed bound to the DNA strand and prevented the cell from initiating the repair process,” Merrill said. The stuck Cas9 is also unable to go on to make additional cuts in DNA, thus limiting the efficiency of CRISPR, he said.

Merrill, UIC graduate student Ryan Clarke, and their colleagues also found that Cas9 was likely to be ineffective at sites in the genome where RNA polymerases — enzymes involved in gene activity — were not active. Further investigation revealed that guiding Cas9 to anneal to just one of the strands making up the DNA double helix promoted interaction between Cas9 and the RNA polymerase, helping to transform a “dud” Cas9 into an efficient genome editor.

Specifically, they found that consistent strand selection for Cas9 during genome editing forced the RNA polymerases to collide with Cas9 in such a way that Cas9 was knocked off the DNA.

“I was shocked that simply choosing one DNA strand over the other had such a powerful effect on genome editing,” said Clarke, the lead author of the paper. “Uncovering the mechanism behind this phenomenon helps us better understand how Cas9 interactions with the genome can cause some editing attempts to fail and that, when designing a genome editing experiment, we can use that understanding to our benefit.”

“This new understanding is important for those of us who need genome editing to work well in the lab and for making genome editing more efficient and safer in future clinical uses,” Merrill said.

The study findings are also significant because, in the genome editing process, the interaction between Cas9 and the DNA strand is now known to be the “rate-limiting step,” said Merrill. This means that it is the slowest part of the process; therefore, changes at this stage have the most potential to impact the overall duration of genome editing.

“If we can reduce the time that Cas9 interacts with the DNA strand, which we now know how to do with an RNA polymerase, we can use less of the enzyme and limit exposure,” Merrill said. “This means we have more potential to limit adverse effects or side effects, which is vital for future therapies that may impact human patients.”

Additional co-authors on the study are Matthew MacDougall, Maureen Regan and Leslyn Hanakahi of UIC; Robert Heller and Dr. Luciano Marraffini of Rockefeller University; and Nan Cher Yeo, Alejandro Chavez and George Church of Harvard Medical School.

Grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01-HD081534 and 1DP2AI104556) and the UIC Center for Clinical and Translational Sciences supported this research. Marraffini and Church both noted financial disclosures relevant to the study.

Source:

Adapted (with modifications) from the UIC today, by Jacqueline Carey, published on July 10, 2018.

Citation:

Clarke R, Heler R, MacDougall MS, Yeo NC, Chavez A, Regan M, Hanakahi L, Church GM, Marraffini LA, Merrill BJ. Enhanced Bacterial Immunity and Mammalian Genome Editing via RNA-Polymerase-Mediated Dislodging of Cas9 from Double-Strand DNA Breaks. Mol Cell. 2018 Jul 5;71(1):42-55.e8. (PubMed)

Featured scientist(s) with ties to cbc:

Bradley Merrill, UIC

- CBC Scholar Program (2013-2014):

▸ Meet the Scholar Brian Shy, UIC, Class of 2013

Bradley Merrill (UIC) — Scholar’s Mentor - CBC Catalyst Award (2014):

▸ Immunotherapy-Mediated Interference of Bacterial Quorum Sensing

PIs: Fotini Gounari (UChicago) and Bradley Merrill (UIC) - CBC Tech Day (2014):

▸ Cutting-Edge Technologies — Driving Science Forward

Bradley Merrill (UIC) — Tech Day Speaker