June 12, 2013

Many Tissues, One Body: Intertissue Collaboration in Stress

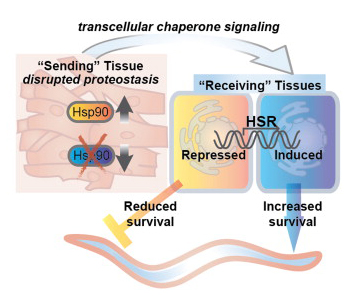

Supported by a CBC Lever Award, Rick Morimoto’s team at NU reported June 6, 2013, in Cell, that, in C. elegans, one damaged tissue not only attempts to self-repair but also alerts other tissues and organs within the body about the ongoing stress. In consequence, the non-harmed but alarmed healthy tissues respond by releasing factors that help to mend the damaged one. This transcellular, intertissue stress detection and signaling mechanism is thought to increase the organism’s chances of survival.

Northwestern University scientists are the first to discover a cellular process used by animals when a tissue is stressed and in molecular trouble from the expression of misfolded and damaged proteins: The tissue at risk attends to the trouble itself but also wisely calls out for help.

In a study of the transparent roundworm C. elegans, the researchers found the entire animal responds to prevent the tissue in trouble — its weakest link — from negatively affecting the survival of the organism.

The stressed tissue sends a multiple-alarm distress call to other tissues throughout the animal, and distant tissues respond, sending biochemical help to restore the protein quality-control system to health and balance.

The stressed tissue sends a multiple-alarm distress call to other tissues throughout the animal, and distant tissues respond, sending biochemical help to restore the protein quality-control system to health and balance.

“Now we know all the tissues are communicating,” said Richard I. Morimoto, who led the research. “It’s a community response. There is a signaling pathway that is used for conversation between tissues, and tissues at risk use it to call for help. When the whole animal doesn’t respond to distress or responds poorly, disease can occur.”

Morimoto is the Bill and Gayle Cook Professor of Biology in the department of molecular biosciences and the Rice Institute for Biomedical Research in Northwestern’s Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences.

Knowledge of the underlying biological structure of cellular communication processes used by multicellular organisms could give scientists a new approach to understanding human disease, particularly protein misfolding diseases such as Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s and Huntington’s diseases, and also could extend more broadly to metabolic disorders and cancer.

Specifically, the research team found that when a muscle tissue is stressed because of expression of a faulty protein in that tissue, it calls in reinforcements, alerting neurons and intestinal cells. All three tissues respond by triggering the heat shock response, an ancient and very powerful mechanism for detecting and responding to protein damage. Functioning proteins keep an animal healthy and long lived.

The findings were published June 6, 2013, in the journal Cell: “Regulation of Organismal Proteostasis by Transcellular Chaperone Signaling”.

Morimoto and his fellow authors, postdoctoral fellow and first author Patricija van Oosten-Hawle (right) and undergraduate student Robert S. Porter, studied C. elegans because its biochemical environment is similar to that of human beings and its genome, or complete genetic sequence, is known.

Morimoto and his fellow authors, postdoctoral fellow and first author Patricija van Oosten-Hawle (right) and undergraduate student Robert S. Porter, studied C. elegans because its biochemical environment is similar to that of human beings and its genome, or complete genetic sequence, is known.

In the study, the researchers took advantage of mutations in muscle cell-specific proteins that cause protein damage to study how the muscle cells with the mutation respond. They found the protective heat shock response is activated in both the distressed tissue (muscle cells) and in distant, unstressed tissue (neuronal cells and intestinal cells).

“This surprised us,” said Morimoto, who also is a scientific director of the Chicago Biomedical Consortium. “Why should the intestine or neurons need to know what is happening in the muscle cells? It is about survival of the animal. Coming to the aid of a stressed tissue benefits the entire organism.”

The damaged protein tells the muscle cell it isn’t optimal, triggering the heat shock response and its special protective molecular chaperones, which correct the damaged proteins. Tissues at a distance also sense the stress, triggering the same heat shock response, which benefits the muscle cells in trouble.

The researchers also discovered that when they increased the levels of molecular chaperones in just the neuronal cells or intestinal cells (not in the muscle cells), the same restoration of protein health in the muscle cells occurred.

The National Institutes of Health, the Ellison Medical Foundation, the Chicago Biomedical Consortium and the Daniel F. and Ada L. Rice Foundation supported the research.

Rick Morimoto is a co-recipient of a CBC Lever Award that helped to establish the Chicago Center for Systems Biology (CCSB), funded by National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS) and hosted at the Institute for Genomics and Systems Biology (IGSB) at the University of Chicago. Patricija van Oosten-Hawle is a recipient of one of the two postdoctoral fellowships from IGSB that have been funded by the CBC Lever Award. The fellowship fulfills one of the CCSB aims, “Establishing a CBC Research Fellows Program in Systems Biology to train the next generation of young scientists in the art of interdisciplinary research in Systems Biology.”

Adapted (with modifications) from: “Tissue in Trouble Calls in Reinforcements to Restore Health” by Megan Fellman, NU News, June 6, 2013

Image Credits: Graphical Abstract (adapted from Cell, top); Patricija van Oosten-Hawle.